张光直:怀念李济(1896~1979)

怀念李济(1896~1979)

张光直

近六十年的岁月里,首先作为中国考古学之父、随后又作为中国考古学掌门人的李济,为人文科学和历史科学作出了不可磨灭的贡献;在中国,他的学术思想至今仍然在他的研究领域占据支配地位。

在湖北出生、在老家和北京成长的李济,他的少年时期正处于这个古老国家在与西方接触的压力下迈开通向现代化漫长道路的最初步伐的时候。就跟现在一样,当时一批批颇有才华的青年学生被送往西方各国去学习它们的科学奥秘。从著名的清华学堂毕业后,李济被送到美国麻省伍斯特市的克拉克大学攻读心理学和社会学,接着又到哈佛去学习人类学。据李济在1977年跟费正清的夫人慰梅女士的一次谈话中说,他之所以去克拉克大学,是因为清华的一位心理学老师华尔考博士跟他说,要学心理学,就要去克拉克。在克拉克时期,李济养成了一个习惯:每个星期六的上午他都去图书馆开架阅览室,尽情浏览各种书刊。在这种啃青草式的阅读中他偶然地接触到自己不曾了解的人类学的书籍,立刻就被这门学问吸引住了。李济于1923年获得哈佛大学博士学位。在这里,他跟从虎藤、托策和狄克森三位老师分别学习了体质人类学、考古学和人种学;这三门学问在他的博士论文写作(1928年正式出版)和随后六十年的学术生涯中全都派上了用场。

从1923年回国到1928年,李济一直担任着一种地道美国式的大学教授兼研究学者的工作。他先后在天津南开大学(1923~1925年)和母校清华大学新成立的国学研究院任教(1925~1928年)。1925到1926年他负责主持了在山西南部夏县西阴村的一个仰韶文化的新石器时代遗址的发掘。这次发掘是由清华的国学研究院和美国华盛顿特区的弗利尔美术馆联合举办的,李济因此成为第一位挖掘考古遗址的中国学者。

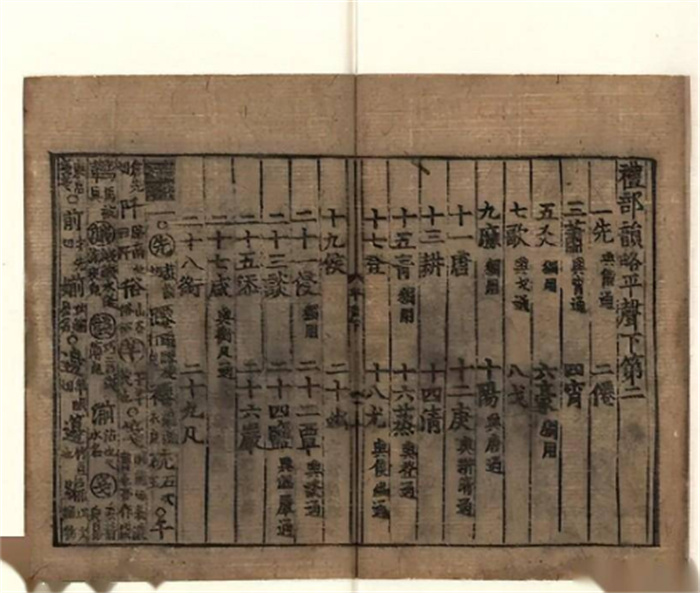

1928这一年是李济一生中的转捩点,也是中国考古学和历史学的转捩点。为了充分估价1928年开始李济所经历事件的重要意义,需要再上溯到近三十年前的1899年,即义和团事件和八国联军入侵的前一年;八国联军的入侵使中华帝国在西方工业大国和军事强国的威力面前蒙受了奇耻大辱。也就是在这一年,商(或殷)代(公元前1766~公元前1122年)的甲骨文在王朝灭亡近三千年之后,首次引起了古史学者们的关注。在此后的三十年里,中国和外国的研究商史的学者们都被这一新的史料来源迷住了,他们大规模地追踪古董市场上流通的这类骨片的出土源头。没过多久,这些学者就察觉到契刻甲骨来自殷墟,即长久以来为人们所知晓的靠近河南北部洹水岸边的现代安阳所在地——殷王朝的废墟。

国民党人在1928年取得了北伐的胜利,在南京建立了新的政府。一个新型的全国性的科学研究机构——“中央研究院”——成立了,研究院内设立了一个国立的历史语言研究所。所长傅斯年曾在德国学习历史学和语言学,他立即为新成立的研究所立下了两个项目:(一)成立一个考古组,作为研究中国历史的新工具;(二)发掘殷墟,作为考古组的第一个田野工作项目。为实现这两件事,傅亟须一位受过西方田野工作传统训练的有资历的考古学家;组主任和发掘项目主持人这二者的必然选择结果,都落在李济身上。从这时开始,李济的学术生涯就和安阳的发掘再也分不开了。“中央研究院”所领导的这一发掘工作一直持续了十五个工作季,直到1937年年中。

如今只有为数很少的人知道,当傅寻找一位合适的学者来领导这个新成立的考古组——这实际意味着挑选一位全国性的考古事业的领导者——时,受到推荐的不是一位、而是两位有力的候选人,这另一位是马衡(1881~1955年)。马是一位备受尊敬的传统古文物研究学者,后来是北京大学考古研究室主任和故宫博物院的院长。不妨设想一下:如果马衡当年成了傅最后选中的人,中国的考古学现在会是一个什么样子?因为1928至1937年的安阳发掘和李济对安阳发掘的领导,对下半个世纪的中国考古学的发展起了决定性的影响。

首先,安阳的发掘确立了商文明在中国古代史上为首的地位,它是整个东亚地区第一个有文字记载的文明。商代是把浩瀚的中国史籍记载和日益增多的史前中国信息体联结起来的一个纽带。然而我们关于商代的知识很大程度上仍是由李济给我们划定的。他组织了在安阳的考古探寻。他使用了西方的考古方法和观念。他招募了众多的同事和学生,并在安阳的实地工作中用这些方法和观念培养他们。这些年轻的学者中包括近三十年活跃在考古界的所有重要人物,包括夏鼐——中国社会科学院考古研究所的所长,包括高去寻——直至1981年夏天的台湾历史语言研究所所长。李济为安阳出土器物的研究定下总基调,并确立了研究的主次性,他的整套研究方法——尤其是陶器和青铜器的命名和类型学方法——一直还在整个中国考古学界处于支配地位。在他本人的研究工作中,他树立了一种高要求的科学标准——他的后继者们都努力在自己的工作中以之为榜样。他既是一个认真守护中国的文化珍品、防范外国盗窃者侵犯的爱国者,又是一个渴望接受西方所可能提供的最佳技术和观念、力求在世界背景下观察和构想中国的国际主义者。他的后继者中有许多人能做到这两者中的一个方面,但很少有人能像他那样有韧性和眼光同时做到两个方面。

1937年7月爆发的抗日战争事实上结束了由李济的考古组所进行的重要田野考古工作;1949年以后,随着蒋介石政府的逃亡,李济也去了台湾。李济从1937年直到1979年逝世,花去大部分时间用于保管、运送、研究和出版1928年至1937年期间安阳出土的资料。虽然因战争而造成的研究生活的不稳定,以及参加安阳工作的考古学家中有些人故去、有些人离去,给李济管理商代遗宝的计划造成不利的影响,但到他去世前,他看到在他的最后一部著作《安阳》(1977年英文版)中撮要概述到的很大一部分资料都已经出版了。完整的报告并没有出来,但是不利的因素已非李济所能控制的了;他已经做到他力所能及的一切,对此我们表示衷心的感谢。我强烈地意识到,李济一生之所以一再拒绝美国一些大学提供职位的邀请、没有像他的一些同事那样在战中或战后移民过去,最根本的原因是,他感到自己必须留在国内,看到安阳研究的全过程。

除了安阳的发掘和研究外,李济还从事了其他许多重要的学术活动,最早是在抗战时期的大西南,1949年以后在台湾。这里仅列举其中的几项:1934年他被任命为中央博物院的筹备主任,从此以后,他成为一个主张历史博物馆应是发掘、研究兼教育的机关的热心拥护者。他的这一理想在近三十年里已在中国得到广泛的实现。1949年他在台北的台湾大学创办了考古人类学系,第一次在中国把培养专业考古学家列入大学计划之内。20世纪60年代初期,他在促成“中央研究院”成立中国古史委员会,着手编写一部多著者、跨学科的中国古史中起到关键作用,此举开中国史学编著之先河。到李济去世时,该书的初稿已开始问世。

我第一次见到李济是在1950年秋季进入台大他创办的新系的时候。这以后的29年里,他是我的老师、导师、批评者、行为榜样和学术良心。当然,我时常感到,李济是一个伟大的历史人物,他塑造了今天中国的考古学;但对于我来说,他最主要的价值就在于他体现了在中国历史学和考古学研究中所能达到的最高科学标准。他对在中国建立科学的学术事业怀有一种纯挚的热忱,并用自己的言行树立了一个令他的后继者渴望达到而又难以企及的榜样。他的过世是世界上一切真正学人的一大损失。

1981年11月19日

Li Chi: 1896-1979

K. C. Chang

After almost sixty years, first as the father and later as the dean of Chinese archaeology, Li Chi has left indelible contributions to the science of humankind and of history, and his thinking still dominates his discipline in China.

Born in Hupei, Li Chi grew up at home and in Peking at a time when the old country, forced by encounters with the West, was taking its initial steps on the long road to modernization. Then, as now, bright young students were sent to Western countries to learn their scientific secrets. After his graduation from the elite Tsinghua Academy, Li Chi was sent to the United States, where he studied psychology and sociology at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, and then anthropology at Harvard. According to an interview with Wilma Fairbank in 1977, Li Chi said that he went to Clark because a psychology teacher at Tsinghua, a Dr. Wolcott, had told him that Clark was the place to be for psychology. While at Clark, Li Chi developed the habit of spending every Saturday morning browsing in the open shelves of the library. There he happened upon anthropology books and was fascinated by this subject, of which he had had no previous knowledge. At Harvard, where he earned a doctorate in 1923, Li Chi studied with Hooten, Tozzer, and Dixon, and from these three mentors he learned, respectively, physical anthropology, archaeology, and ethnology, all of which he made use of, both in his doctoral dissertation (1928) and in his subsequent sixty-year career in China.

From 1923, when he returned to China, to 1928, Li Chi was the typical university professor-cum-research scholar in the American mold. He taught at Nan-k’ai University in Tientsin (1923-1925) and then at his alma mater Tsinghua Academy’s new Graduate Research Institute (1925-1928). From 1925 to 1926 he undertook the excavation of a Neolithic Yang-shao Culture site at Hsi-yin-ts’un in Hsia Hsien, southern Shansi, under the joint auspices of the Tsinghua Institute and the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D. C., becoming the first Chinese scholar to dig an archaeological site.

The year 1928 was a turning point in Li Chi’s life, and it was a turning point in Chinese archaeology and historiography as well. To appreciate fully the significance of events surrounding Li Chi beginning in 1928 we must go back some thirty years, to 1899, one year before the Boxers and the Allied Invasion which wrought Imperial China’s ultimate humiliation in the face of the industrial and military might of the West. In that year oracle bone inscriptions of the Shang (or Yin) Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.) came to the attention of ancient historians for the first time since the dynasty’s fall three thousand years previously, and during the next thirty years Shang scholars within and outside of China became fascinated by this new historiographic source material and launched extensive efforts to track down the bones floating on the antiquities market. Before long, the scholars became aware that these inscribed bones had come from Yin Hsü, the ruins of the Yin Dynasty, long known to be on the banks of the river Huan, near the modern city of An-yang, in northern Honan.

In 1928, the Nationalists succeeded in their Northern Expedition and founded a new regime in Nanking. A new national academy of sciences—Academia Sinica—was established, and under it there was a National Research Institute of History and Philology. The institute’s director, Fu Ssu-nien, who had studied historiography and philology in Germany, decided at once on two projects, among others, for the new institute to launch—to establish a department of archaeology as a new instrument to investigate Chinese history; and to carry out an excavation at Yin Hsü as the department’s first field project. For both, Fu needed a senior archaeologist trained in the Western tradition of field investigations, and Li Chi was a logical choice for both department chairman and excavation project director. From then on, Li Chi’s career became inextricably linked with the An-yang excavations, which, under Academia Sinica, lasted for fifteen field seasons, until the middle of 1937.

It is known to only a very few people now that when Fu was looking for a suitable scholar to head the new archaeology department—thus choosing, in effect, the national leader of archaeology—he had recommended to him not one, but two strong candidates, the other being Ma Heng (1881-1955), a highly respected scholar of the traditional antiquarian mold, later to become chairman of the Research Section of Archaeology of Peking University and director of the Palace Museum. It would be interesting to speculate what Chinese archaeology would be like now had Ma Heng been Fu’s final choice, for the An-yang excavations of 1928-1937 and Li Chi’s direction of them were to shape Chinese archaeology for the next half century.

First of all, the An-yang excavations established the status of the Shang civilization at the head of the ancient history of China as the first civilization in the whole eastern half of Asia with written documents. Shang is the linchpin that ties together the vast recorded history of China with the increasing body of information about prehistoric China. But our knowledge of the Shang has to a great extent been shaped by Li Chi. He organized the search at An-yang for archaeological sites. He applied Western archaeological methods and concepts. He recruited colleagues and students and trained them in these methods and concepts at An-yang. Among these younger scholars were all the leading archaeologists active in China in the last thirty years, including Hsia Nai, director of the Institute of Archaeology, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and Kao Ch’ü-hsun, until summer 1981 director of the Institute of History and Philology in Taiwan. Li Chi also set both the tone and the priorities of the study of the An-yang finds, and his methodology—above all ceramic and bronze vessel nomenclature and typology—still dominates the whole field of archaeology in China. In his own research he set a high standard of scientific excellence, which his successors struggle to measure up to in their own works. He was also both a patriot, jealously guarding China’s cultural treasures against foreign pilferage, and an internationalist eager to adopt the best techniques and ideas the West had to offer and to view and conceptualize about China in the world setting. Many of his successors have succeeded in being one or the other, but few have equalled his tenacity and vision to be both.

The Sino-Japanese War that broke out in July 1937 virtually put an end to further archaeological fieldwork of significance being carried out by Li Chi’s department, and after 1949 he went to Taiwan with the exiled government of Chiang Kai-shek. From 1937 until his death in 1979, Li Chi spent much of his time dealing with the care, transportation, study, and publication of the An-yang material excavated during the 1928-1937 interval. Although the war-caused instability of institute life and the deaths and departures of many of the An-yang archaeologists had adversely affected Li Chi’s plans for the Shang treasure, by the time of his death he had seen the publication of the bulk of the material, which he summarized in his last book Anyang (1977). The whole report is not out, but the adverse factors were beyond Li Chi’s control, and he did everything he could have done, for which we are truly grateful. I have a strong feeling that the reason Li Chi declined repeated offers of university posts in the United States, to which some of his Academia Sinica colleagues immigrated during and after the war, was primarily because he felt he had to stay in China to see the Anyang studies through.

Outside his An-yang work, Li Chi was engaged in many other significant scholar activities, first during the war in the Southwest and, after 1949, in Taiwan. Among them we may name the following. In 1934 he was appointed to head the Central Museum, and from then on he was an ardent espouser of historical museums as organs of excavation, research, and education. This ideal has been put into practice extensively throughout China during the last thirty years. In 1949 he founded the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the National Taiwan University in Taipei, the first university program in China to train professional archaeologists. In the early 1960s he was instrumental in the organization, under Academia Sinica, of a committee on the ancient history of China to launch the preparation of a multiauthored, interdisciplinary volume on ancient Chinese history, the first such effort in Chinese historiography. By the time of his death the first drafts of this volume were beginning to appear.

I first met Li Chi in the fall of 1950, when I was admitted to his new department at Taiwan University. For the next twenty-nine years he was my teacher, mentor, critic, role model, and academic conscience. I was always conscious, of course, that Li Chi was a great historical figure, who had given archaeology in China its present shape. But above all he meant just one thing to me—he embodied the highest scientific standard that could be achieved in the study of Chinese history and archaeology. He had a single-minded devotion to scientific scholarship in China and by his own word and deed set a forbidding model for his followers to aspire to. His death is a gigantic loss for all true scholars of the world.

- 0000

- 0000

- 0000

- 0000

- 0000